Approximately 80% of the world’s population is unable to access educational content published in English (Beaven, Comas-Quinn, de los Arcos, & Hauck, 2013). Massive open online courses (MOOCs) have the potential to provide educational opportunities across geographic, linguistic and cultural boundaries that would otherwise be difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. The core content of a MOOC is really no different than the core content of any online course; it is designed and taught in one language, typically by designers from one culture. It is the massiveness and openness that changes an online course into a system in which information is re-transmitted, shared, and adapted to participant needs. Solitary participants from remote areas have the opportunity to interact with other experts and learners in specialized areas through the MOOC environment. The result is a growing democratization of access to information and a diminishing language barrier.

One of the adaptations needed when participation in a MOOC grows and crosses international lines is the need for translation into other languages. Simon Thrun and Peter Norvig of Stanford taught one of the earliest MOOCs, Introduction to Artificial Intelligence (Rodriguez, 2012). It was offered free to anyone in the world, and attracted 160,000 enrollees. Of those, 20,000 from 190 different countries completed the course. With the help of more than 2,000 volunteers, the course was translated into 44 different languages (Murray, 2012). In an unplanned, grassroots movement, many participants connected on social media as well, in languages other than English, making the MOOC both more accessible and more relevant to their needs (Murray, 2012).

Coursera provides an ongoing example of an approach to overcoming geographinc, linguistic, and cultural boundaries. Coursera is a non-profit organization started out of Stanford University in 2012 that partners with universities around the world in order to provide free, high-quality MOOCs that are open to anyone in the world. That mission requires dealing with the issue of language. The mission of the Coursera project is “to connect the world to a great education. To do so, we have to overcome language barriers, which can be very real obstacles for our students who come from all over the world.” (Coursera, 2013). After one year of providing courses in English, Coursera formed the Global Translations Partners Program in order to begin the process of translating courses into Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, Kazakh, Portuguese, Russian, Turkish, and Ukrainian, with more languages to follow. Reaching 5.2 million users after only 18 months of existence, this project is worth noting because of its scale and because it is taking a lead role in modeling global access to the highest quality learning.

MOOCs and translation projects like the ones cited here have shown the potential to build language bridges across spans that would otherwise have seemed impassable. The nature of MOOCs leads to collaborative solving of the inherent language issues of the Internet.

References

A glimpse into my experiences learning and leading with educational technology.

Monday, October 28, 2013

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Academic Vocabulary

| CC image by lisa31337 on Flickr |

Take, for example, the p value, which is computed using a t-test. The p value is also called the level of significance, and we want it to be as low as possible. A high level of significance means there is likely no significant difference between two tests. So essentially, a statistician wants a low level of significance in order to prove the significance of a comparison. To make things more interesting, when you conduct a t-test comparison in SPSS which is supposed to yield a p value, there is no p-value. There is a t value, which has nothing to do with the t in the t-test. There are 2 “sig” columns, but we aren’t currently worried about the one that goes with Levene's Test for Equality of Variances.

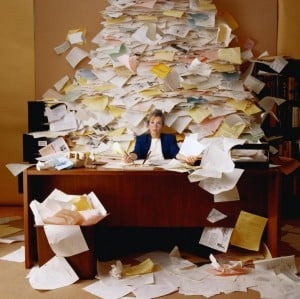

Even with a class glossary, 2 textbooks, and YouTube to help me make sense of things, I’m drowning in the new vocabulary. The base concepts themselves aren’t actually that complicated, but trying to read and write in the correct vocabulary is. There are concepts and comparisons I can draw, but I lose points in my descriptions because I use the wrong terms. On the plus side, I definitely have a much better gut-level understanding of what our English Language Learners are going through as they try to tackle complex vocabulary in the content areas.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Organizing my life. Or at least my blog!

This past week I was taking a look back at my blog and I realized how many different functions it has served for me. Originally, I wanted a space to reflect on my practice. My first post, in late December 2011, set out my goals for blogging:

In the spring of 2012, I started using my blog to respond to assignments in various courses I was enrolled in. And then I made a blog post that was part of my doctoral application. There are now blog posts about online learning, about online leadership, about social media, and even about statistics. Some of those blog posts were spontaneous based on my learning, but some were mandated by courses I took. Even in required blog posts, I am trying to make sure that my voice stays consistent, and that I am continuing to learn not just from the assignment but from sharing the assignment.

Now I'm thinking that I ought to start categorizing my posts, to make it easier to go back and revisit themes. I started adding some labels to more recent posts, but then I realized I need to really think about what those labels are. What are the themes I might want to look back through and reflect on my personal growth and changes? What are the themes I might want to capture as a record of my academic work? Is there value to adding labels for themes that are no longer relevant to me in my current position?

So, right now I'm considering the following labels:

- I will be a reflective practitioner of my craft.

- I will share what I have learned.

- I will learn from what I share

I will bring balance to my chaos.(I've given up on this one!)

In the spring of 2012, I started using my blog to respond to assignments in various courses I was enrolled in. And then I made a blog post that was part of my doctoral application. There are now blog posts about online learning, about online leadership, about social media, and even about statistics. Some of those blog posts were spontaneous based on my learning, but some were mandated by courses I took. Even in required blog posts, I am trying to make sure that my voice stays consistent, and that I am continuing to learn not just from the assignment but from sharing the assignment.

|

| CC Licensed Image |

So, right now I'm considering the following labels:

- BSU (for all course required blog posts)

- Online learning

- Leadership

- Administration (for job-related things)

- K-6 (for school-related things)

- Learning (for general a-ha's and reflections related to my own professional and/or personal growth)

Sunday, October 6, 2013

Global Responses to Digital Textbooks

Digital textbooks are the new norm, at least where I live. In California, there is legislation requiring publishers who submit for adoption to include a digital edition of their textbook. In my district, students have access to their textbooks through the LMS. However, according to Stephen Asunka's article in Open Learning, The Viability of e-Textbooks in Developing Countries, positive beliefs about e-textbooks are far from universal.

This study explored levels of student awareness of and experiences with e-textbooks at a private ICT-driven university in Ghana. The purpose of the study was to gain insight into the e-textbook deployment in sub-Saharan higher education, and establish a baseline of perceptions and use that can be used to measure changes in behaviors and practices. The study did not rely on any standard theoretical framework, "because e-books are a fairly novel (and rapidly evolving) phenomenon in the developing world" (p. 41). While e-textbooks are a novelty in sub-Saharan Africa in general, because of the type of university used as a participant pool, survey participants were 99% familiar with what an e-textbook was. The researcher used a survey questionnaire that focused on usage and attitude towards e-textbooks to gather data, including both qualitative and quantitative measures.

Few students in the study were aware of multimedia and/or interactive features of e-textbooks. The researcher speculated that this might be due to Ghana's limited high bandwidth access, and the high cost of internet access outside of the university environs. In addition, the vast majority of students who used e-textbooks accessed them through a computer, with very few students indicating that they used dedicated readers or handheld devices. Most students indicated that they preferred print textbooks because of their convenience and accessibility.

In most of the United States, along with most developed nations, access to high-speed internet bandwidth at low or no cost is a given. In every large city and town, as well as most small ones, individuals can get online at fast food restaurants, coffee shops, and public areas without cost. Digital textbooks are becoming more common as early as elementary school, and students are explicitly taught to use the interactive features built into e-textbooks. Dwyer & Davidson's (2013) review of literature over the past decade shows increasing access to and comfort with e-textbooks at universities in the United States. In 2011, Bob Minzesheimer of USA Today noted that for four of the top ten best-sellers, digital editions outsold print editions. Now, USA Today (as well as other best-seller lists) no longer differentiate between print and digital editions in their lists. This appears to indicate that, at least in the United States, e-texts have attained widespread acceptance and use.

And yet in their 2013 study, Dwyer & Davidson found that many university students did NOT like using e-textbooks. Many complained about eye strain and lighting, or inability to highlight text or add notes. The researchers conclude that "e-textbooks are not at the place where students are embracing them" (p. 120).

These articles, combined with my own experience, underscore the role of culture and environment in tool adoption. There are some base underlying conditions that allow any culture to evolve. The invention of irrigation allowed for surplus which allowed for development of leisure pursuits such as the arts. Access to bandwidth and devices allow for implementation of digital texts which allow for the development of a comfort with this type of interaction. Students in Ghana, having little access to e-textbooks because of infrastructure limitations, find the use of digital textbooks to be awkward. In US universities, students have significantly better access, but also find the use to be awkward, albeit for different reasons and to a lesser degree. It might just be that we are in the transition, and the trend we see of increased access, increasing use of e-books, and improved interactivity features will continue to facilitate the growth of e-textbook use.

In my own experience using e-texts, there is a comfort curve. Before I read my first digital text, I was firmly convinced that it would be a niche use for me, not my normal reading habit. Over time, however, reading everything from the newspaper to leisure reading to textbooks on my iPad has become my norm. I still love going to a bookstore to browse, but I"m getting better at browsing e-book stores in a way that helps me select what to read next. My nieces and nephews are comfortable reading on a digital reader, including highlighting and note-taking. In my district, students at middle and high school prefer the e-reader to textbooks. To be fair, that's probably about weight, and they are no more likely to look at the textbook on their device than they were when it was in print!

Asunka, S. (2013). The viability of e-textbooks in developing countries: Ghanaian university students’ perceptions. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e- Learning, 28(1), 36-50, DOI: 10.1080/02680513.2013.796285

This study explored levels of student awareness of and experiences with e-textbooks at a private ICT-driven university in Ghana. The purpose of the study was to gain insight into the e-textbook deployment in sub-Saharan higher education, and establish a baseline of perceptions and use that can be used to measure changes in behaviors and practices. The study did not rely on any standard theoretical framework, "because e-books are a fairly novel (and rapidly evolving) phenomenon in the developing world" (p. 41). While e-textbooks are a novelty in sub-Saharan Africa in general, because of the type of university used as a participant pool, survey participants were 99% familiar with what an e-textbook was. The researcher used a survey questionnaire that focused on usage and attitude towards e-textbooks to gather data, including both qualitative and quantitative measures.

Few students in the study were aware of multimedia and/or interactive features of e-textbooks. The researcher speculated that this might be due to Ghana's limited high bandwidth access, and the high cost of internet access outside of the university environs. In addition, the vast majority of students who used e-textbooks accessed them through a computer, with very few students indicating that they used dedicated readers or handheld devices. Most students indicated that they preferred print textbooks because of their convenience and accessibility.

|

| PresenterMedia licensed image |

And yet in their 2013 study, Dwyer & Davidson found that many university students did NOT like using e-textbooks. Many complained about eye strain and lighting, or inability to highlight text or add notes. The researchers conclude that "e-textbooks are not at the place where students are embracing them" (p. 120).

These articles, combined with my own experience, underscore the role of culture and environment in tool adoption. There are some base underlying conditions that allow any culture to evolve. The invention of irrigation allowed for surplus which allowed for development of leisure pursuits such as the arts. Access to bandwidth and devices allow for implementation of digital texts which allow for the development of a comfort with this type of interaction. Students in Ghana, having little access to e-textbooks because of infrastructure limitations, find the use of digital textbooks to be awkward. In US universities, students have significantly better access, but also find the use to be awkward, albeit for different reasons and to a lesser degree. It might just be that we are in the transition, and the trend we see of increased access, increasing use of e-books, and improved interactivity features will continue to facilitate the growth of e-textbook use.

In my own experience using e-texts, there is a comfort curve. Before I read my first digital text, I was firmly convinced that it would be a niche use for me, not my normal reading habit. Over time, however, reading everything from the newspaper to leisure reading to textbooks on my iPad has become my norm. I still love going to a bookstore to browse, but I"m getting better at browsing e-book stores in a way that helps me select what to read next. My nieces and nephews are comfortable reading on a digital reader, including highlighting and note-taking. In my district, students at middle and high school prefer the e-reader to textbooks. To be fair, that's probably about weight, and they are no more likely to look at the textbook on their device than they were when it was in print!

Asunka, S. (2013). The viability of e-textbooks in developing countries: Ghanaian university students’ perceptions. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e- Learning, 28(1), 36-50, DOI: 10.1080/02680513.2013.796285

Dwyer, K. K. & Davidson, M. M. (2013). General education oral communication assessment and student preferences for learning: E-textbook versus paper textbook. Communication Teacher, 27(2), 111-125, DOI: 10.1080/17404622.2012.752514

Minzesheimer, B. (2011, August 11). E-books jet to top 10 of USA TODAY's Best-Selling Books list. USA Today. Retrieved from http://books.usatoday.com/bookbuzz/post/2011/08/e-books-jet-to-top-10-of-usa-todays-best-selling-books-list/414589/1

Thursday, October 3, 2013

Purpose of Evaluation

There is a longstanding debate about the purpose of teacher evaluation. Is the purpose to improve teacher practice through reflective conversation and expert advice? Is it to measure teacher competence? Or is it somewhere between those two, reflecting elements of both? An article last year in Educational Leadership addressed the question by asking practitioners what they thought to be the purpose of teacher evaluation. The vast majority of respondents said that evaluation was both improvement of practice and measurement, with an emphasis on improving practice.

As I begin my first formal teacher observations of the year, I couldn't agree more. It is critical to have standards of professional practice, and a clear understanding of what those standards look like. In my district, we have expectations about the types of instruction that will take place, the need for a variety of engagement strategies, requirements on ELD support, and a vision of what classroom environment should include. Those are the items we use to measure teacher competence. But it is the informal and formal observations that happen at least a couple of times a month, and the short reflective conversations those observations provoke, that drive teacher improvement. As I visit classrooms, I focus on one or two areas, looking for evidence of proficiency. Often I find it. Part of the conversation I have with teachers afterwards asks how or why they made the choices they did, and reinforcing that their decision-making was sound. Sometimes I don't find the evidence I'm looking for. So the conversation starts with whether I just missed the evidence, as I ask them to describe what that practice or strategy looks like in their classroom.

At this point in the year (and in my site administrative career), I'm trying to be careful with directives. It seems to me that a first step for teachers who have gaps in their proficiency is to make sure they are exposed to best practices, so having them observe a strategy in a team-member's classroom is a good fit. I can then talk with the teachers as they identify what steps they will take, and the mandate comes from themselves. Later in the year I may need to provide more explicit directives, but for now I think the best intervention is one they pick for themselves.

I believe that my role as a teacher evaluator is to help teachers realize their best student-focused, research-driven, multi-faceted selves. As I do evaluations this year, I need to keep in mind what success in the process looks like from my end - I am doing my job well if teachers are more closely aligned to the expected competencies and are more reflective practitioners by the end of the year.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)